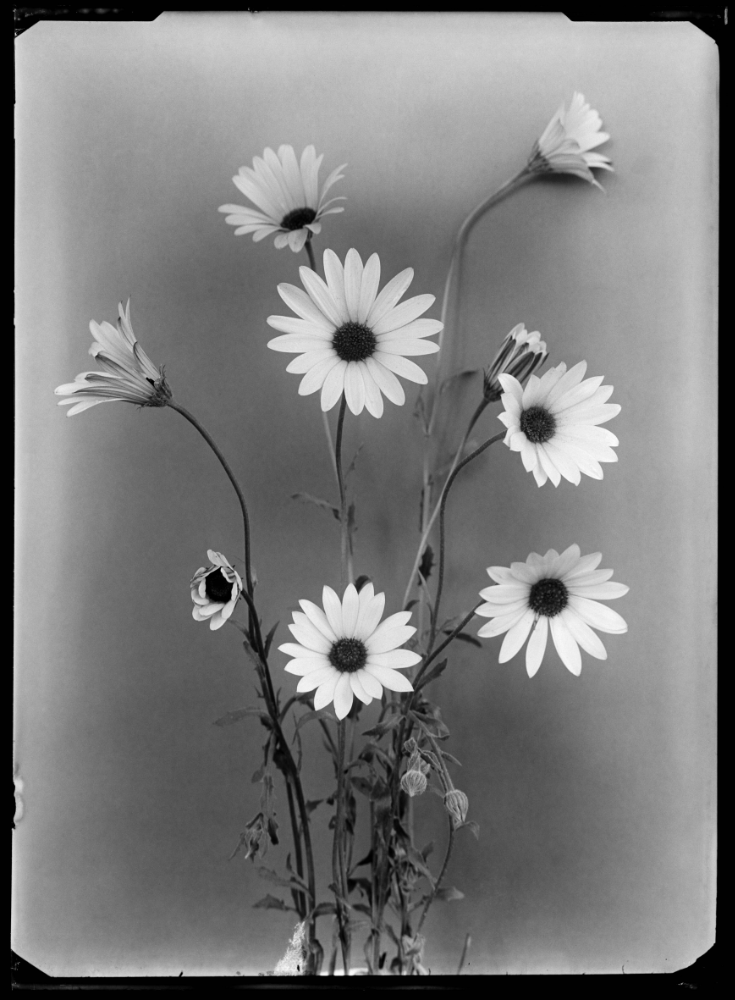

Richard Tepe, 1916. Gelatin negative on glass. Inv. no. TEP-2669.Collection Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam / Public Domain.

Did you know that January 1st is more than New Year’s Day; a day for sleeping in after a New Year’s party, eating left-over “oliebollen” from the night before and visiting family to wish your loved ones the best for the coming year? New Year’s Day also marks Public Domain Day; the day when copyrights expire on texts, artworks and the like, of which the maker passed away 71 years ago. These “products” thus become public domain, which means that anyone anywhere can use the materials in whatever way they like. You could use a world-famous text by an even more famous author as part of a play you are creating as an amateur playwright or print it on your wall at home in jumbo-sized lettering if you like. The Rijksmuseum, for example, encourages people to download the high-resolution image of their favourite artwork from the museum’s collection website, most of which is freely available, and have it printed on a duvet set.[1]

So this January 1st marks another “load” of wonderful material moving into the public domain. So too is the photographic archive of Dutch nature photographer Richard Tepe, which is in the collection of the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam. Together with his colleague P.L. Steenhuizen, Tepe was one of the pioneers of nature photography in The Netherlands. The earliest images from his oeuvre are from around the 1900s. Around this time, attention arose to the presence and disappearance of plant- and animal species in The Netherlands. Tepe, as a photo-pioneer, took it upon himself to register these (disappearing) species on the photographic glass plate. When he started out, he mostly photographed birds, which was quite the undertaking with his sluggish glass plate cameras in combination with the skittish subjects.[2]

In some forty years, from around 1900 to 1940, Richard Tepe amassed an archive of more than three thousand photographic glass plate images. After his death in 1952, these plates were cared for by the Koninklijke Nederlandse Natuurhistorische Vereniging. Some thirty years later they were sold at an auction and eventually ended up in the depots of the Nederlands Fotoarchief, which later merged into the current Nederlands Fotomuseum.[3] The plates have since been repacked into acid-free archival paper four-flaps and fitting boxes, and are kept under ideal climatological circumstances for the materials in order to preserve them for as long as possible.[4] Information about each plate has also been logged in the collection database. One of the most charming parts of this archive is the notes Tepe himself kept about his plates, which provide valuable information about the subject matter and the date the image was procured, but also about some more technical aspects such as the plate type and developer used.

In 1898 Richard Tepe was the first Dutch photographer to photograph a bird’s nest.[5] This was a huge milestone in Dutch nature photography because a scene like this had never before been recorded on a photographic plate.[6] This pioneering image and its 3000+ “siblings” have now been tipped out of the nest and can spread their wings in the public domain.

Enjoy!

[1] Rijksmuseum zet werken online | De Volkskrant

[2] Fotografen (nederlandsfotomuseum.nl)

[3] Depth of Field | Scherptediepte <!– Richard Tepe : depthoffield –> (universiteitleiden.nl)

[4] Mind you, we still don’t know how long these early examples of photography will “last”. The medium is still too young for us to know exactly how long it takes for the photosensitive emulsions and their base materials to deteriorate beyond repair, or vanish completely. Of course, we, being photo historians and photo restorers, have experience with specimens which were badly cared for and therefore deteriorated way quicker. But we still don’t know for sure how long well-preserved specimens will last under ideal circumstances for preservation, or if these circumstances that we so minutely provide and monitor are even ideal at all!

[5] Collecties | Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam

[6] Harrevelt, Loes van. Jacht met de camera. Nederlands Fotomuseum, 2016.

Do you like what we are doing? Support us on Ko-fi.